Smarter Planning for Rural Communities

Planning is the mechanism through which communities control their destinies. It reflects the principle that people should accept what they cannot change, have the courage to change what they must, and achieve the wisdom to know the difference. It is the antithesis of complaining, and blaming, and praying for miracles. This is particularly urgent in the many rural communities.

The Problems

Rural communities face various challenges that can be addressed through planning:

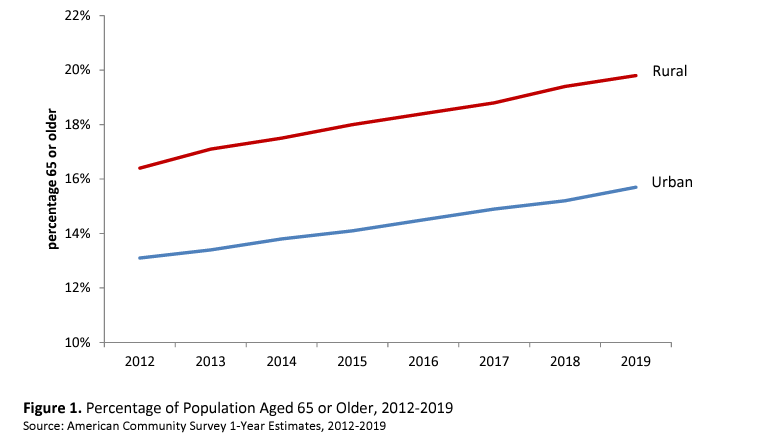

Percent of Population Aged 65 or Older

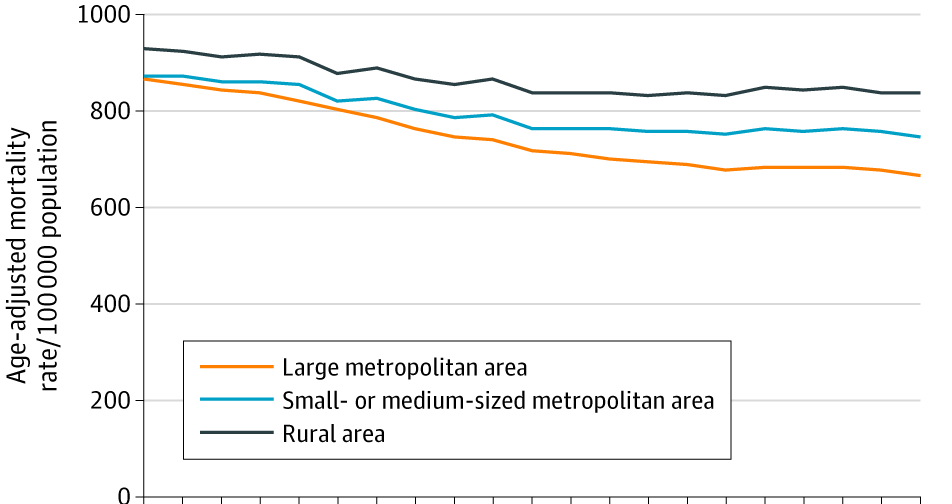

Rural-Urban Disparities in Mortality in the US from 1999 to 2019

This is not to suggest that rural communities are “bad” or that everybody should live in cities; every community type has advantages and disadvantages, as summarized below. However, every community, including rural areas, need to honestly assess their strengths and weaknesses, evaluate problems and plan solutions.

Advantages of Rural and Urban Geographies

Rural | Urban |

Lower-density = more land per capita More proximity to nature More traditional industries Less congestion Less exposure to noise and air pollution Slower demographic change More traditional culture | Greater economic productivity More economic innovation More economic opportunities Greater proximity reduces transportation costs More dynamic change More demographic and cultural diversity More tolerance of diversity |

Who is to Blame?

Most of the previously identified problems reflect a combination of structural and demographic factors, such as those described below.

Structural/Physical | Social/Demographic |

Physical isolation Higher transportation costs Higher costs of providing public utilities and services Less diverse services and industries | Older Poorer More stable (more likely to live in their birth community, with established social networks) More traditional values More culturally homogenous |

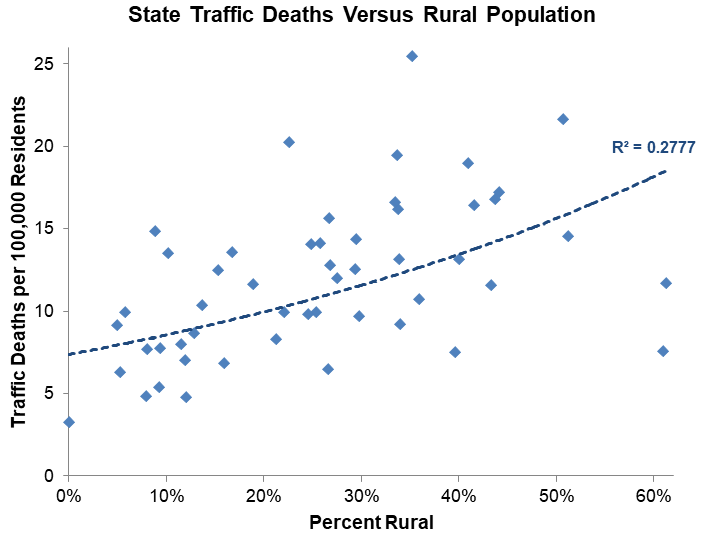

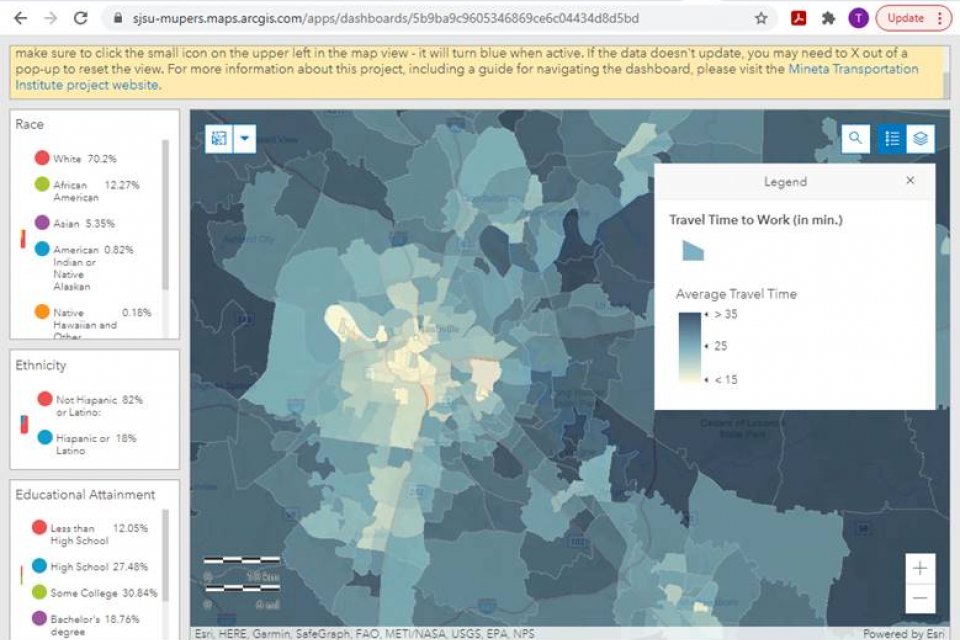

For example, because people are more dispersed, rural residents must spend more time and money on transportation, and are more vulnerable to transportation problems, for example, if their vehicle fails, they lose their ability to drive, or fuel prices spike. In addition, it costs more to provide public services, such as roads, emergency response, schools, and healthcare in rural areas.

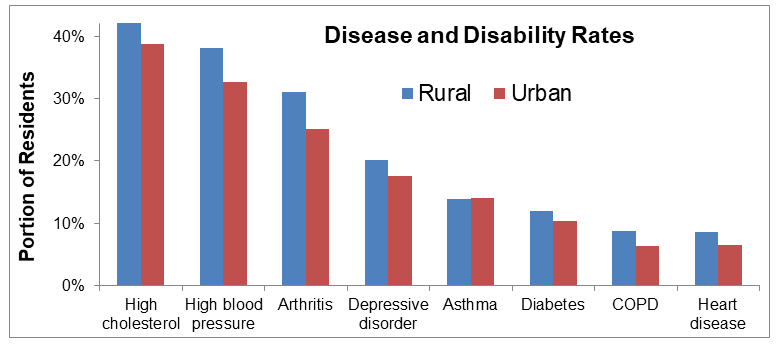

Traditionally, rural residents accepted lower-quality services, such as unpaved roads, volunteer fire departments and one-room schools, but increasingly, rural residents demand higher quality services, despite their high costs. If measured based on outcomes, such as number of doctors per capita, the quality of healthcare services available in a community, or residents lifespans, you could conclude that rural residents are treated unfairly, but measure based on inputs, such as per capita federal and state spending, rural residents receive significantly more, indicating that their public services are subsidized by rural residents. This reflects a combination of structural conditions, due to the higher costs of providing public services in dispersed areas, and demographics, since rural residents tend to be older, less healthy and poorer, and so depend more on public services and assistance programs.

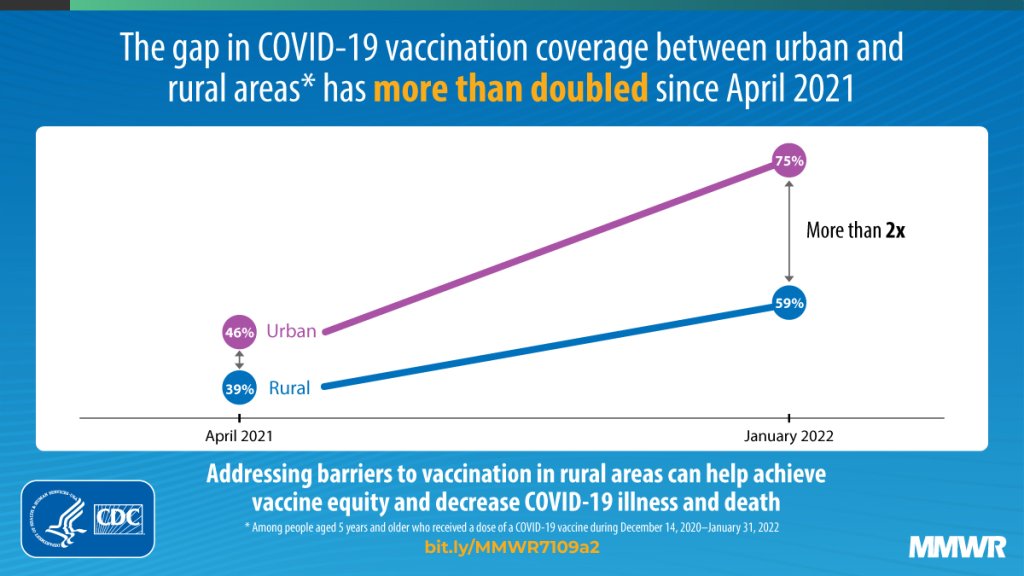

Many of the problems identified above are exacerbated by risky behaviors. Rural residents are less likely to wear seatbelts, exercise regularly, or be inoculated against diseases than urbanites. Rural residents also have lower education attainment, in part because some disrespect higher education and professional expertise. Such practices and attitudes must change for rural communities to become healthier and more economically successful.

In my consulting practice I have worked with many rural communities and small towns. These have generally been very positive experiences, but I also see some difficulties. Too often, rural community advocates complain and blame rather than search for solutions within their control.

For example, I recently participated in a Sustainable Rural Transportation panel at McGill University’s Sustainability Research Symposium. My presentation reviewed the transportation problems facing rural communities and recommended various multimodal planning strategies – pedestrian and bicycling improvements, and innovative public transit funding strategies. However, other panel members insisted on framing rural communities as victims. They argued that rural communities lack public transit services because they don’t receive their fair share of provincial/state/federal transit funding. That misrepresents how public transit services operate. Transit systems are initiated by local governments who provide base funding, and create a management organization which may apply for and receive additional external funds, usually for capital projects (purchasing vehicles and building facilities). Similarly, pedestrian and bicycle facility development, and complete streets roadway design, are primarily local policies. A community that lacks walking and bicycling facilities or transit services should primarily blame itself.

Similarly, Michael Hibbard and Kathryn I. Frank’s recent article, “Bringing Rurality Back to Planning Culture,” claims that planning is biased in favor of urban culture and against rural communities. I don’t think that their arguments make sense, and their conclusions encourage complaining and blaming rather than smart planning. Contrary to their claims, the field of planning is diverse; it includes regional, landscape, watershed, resource, and provincial/state planning that give ample recognition to rural conditions. There is no reason to argue that rural communities victims of urban planning bias.

Hibbard and Frank claim that, “Urban culture, and thus planning, tends to prioritize efficiency over community. Planning would better attend to the challenges facing rural areas if it recognized that rural culture prioritizes community over efficiency.” I can understand why they reach that conclusion, but I think they are wrong.

Many rural residents could earn more money if they moved to a city, but choose to stay; they prioritize community over money. However, urbanites make similar trade-offs; many choose less lucrative jobs because we love the work, or work less to have more time to spend with family or an avocation.

In addition, because public services have higher unit costs in rural areas, and many rural communities are losing population, residents often lobby to retain local services — schools, healthcare facilities, post offices, etc. — despite their cost inefficiency. From residents’ perspective, preserving these services values community over efficiency. However, that misrepresents the issue. It concerns equity not efficiency; it is unfair that rural residents receive far more public investment per capita than urban residents.

Hibbard and Frank claim that, “Planning would better attend to the challenges facing rural areas if it recognized that in rural culture the economy is not just a way to make a living, it is a way of life.” This is another unfair claim. In fact, urban communities are full of people who dedicate their lives to rewarding but unlucrative careers, including artists, non-profit organization leaders, and owners of small, specialized businesses.

Similarly, Hibbard and Frank claim that, “both resource production and conservation primarily benefit urban people and that rural culture prioritizes working landscapes and multifunctional approaches to land use, with multiple socioeconomic and ecological benefits and urban–rural linkages.” This is another understandable, but I believe inaccurate claim. As Nathan Arnosti and Amy Liu point out in Why Rural America Needs Cities, there are actually more resources flowing from cities to rural communities than vice versa. Yes, rural areas produce agricultural and natural resources, but these commodities are available from many sources, while cities provide services and opportunities, such as education and healthcare, and jobs, on which nearby rural communities depend.

Yes, rural culture often does prioritize working landscapes over ecological conservation, because they have a conflict of interest. Many rural communities depend on extraction industries and so are willing to sacrifice their long-term environmental quality for the sake of short-term jobs and tax revenues. It is bad enough that rural citizens allow local environmental degradation, but it is tragic and unfair that rural citizens often elect leaders who block resource conservation initiatives. It is simply untrue that resource production primarily benefit urbanites: on the contrary, because city living is more resource-efficient, in particular an urban lifestyle requires far less energy for transportation and housing, we need far less resource production per capita than rural residents.

Hibbard and Frank are also wrong to claim that resource conservation primarily benefits urbanites. Rural residents can actually benefit a lot, for example, if restrictions on open-pit mining and fracking, and more multimodal transportation planning, make rural communities healthier and safer.

Beyond the Myths

One obstacle to rural planning is the popularity of various myths about the superiority of rural living and the inferiority of cities. Many are long-established: Thomas Jefferson praised hard-working yeoman farmers, Henry David Thoreau advocated a simpler rural life, Will Rogers shared rural wit and wisdom, country western music celebrates rural lifestyles, and Wendell Berry acclaims rural communities in charming poems. They reflect the premise that rural people are more authentic, responsible, and wiser than their urban peers.

Like many myths, there may be a kernel of truth. Rural communities do tend to be more stable — residents are more likely to live in the community where they were born — so rural areas retain older traditions, cultures and values. These may sometimes be desirable attributes, but they are not really unique to urban areas, nor are they entirely good.

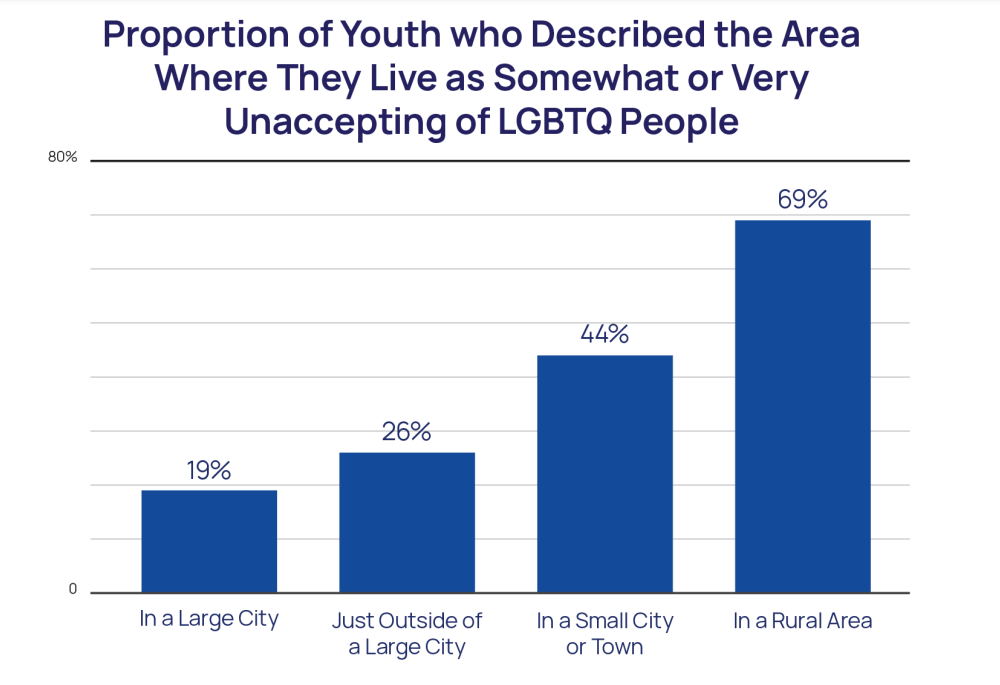

In fact, many traditions, cultures and values thrive in urban areas, including diverse immigrant and ethnic groups, gay and artistic communities. Is there any reason to value rural over urban culture? Are the music traditions of rural Appalachia or the Mississippi Delta than the music traditions of urban Motown, klezmer, or Hip Hop? I can’t see why. Some of the preference for rural over urban culture is thinly-veiled racism; a preference for old, white culture over minority, immigrant, youth culture.

I believe that Hibbard and Frank are wrong to claim that rural residents place more value on community than urban residents. Show me evidence! Rural areas may be very friendly and supportive to members, but can be unaccommodating and cruel to anybody deemed an outsider. Moving from a rural to an urban community can be traumatic — it takes time to develop friendships and build a new community — so it is understandable that many rural people consider cities unfriendly, but I can report from personal experience that residents in my urban neighborhood place a great value on community: we know and support each other, are highly involved in local organizations, and are welcoming to newcomers.

Certainly, there are differences between urban and rural areas — although far less than often portrayed. Urban and rural residents both value community, although in somewhat different ways. Rural areas tend to be more exclusive, placing a higher value on multi-generational families, traditions and conformity. Urban communities tend to be more inclusive, more accepting of diversity and change. Neither is better or worse, all should be treated with respect, and there are often exceptions — many rural communities have pockets of progressives, and many urban neighborhoods have very traditional groups.

Common Obstacles

Rural communities face several possible obstacles to smart problem solving:

- Denial. People refuse to acknowledge the problems facing their community.

- Blaming. Residents consider themselves victims and search for an outsider to blame, rather than taking responsibility and searching for solutions within their control.

- Magic thinking. People hope that a problem will solve itself, or be solved by a single simple action.

- Insularity. Residents reject information or ideas provided by outsiders.

- Defensiveness. I expect that some readers will respond to this column by asking, “Why pick on rural communities? Urban communities have problems too!” That misses the point; this is not a contest, its a problem-solving exercise. Yes, urban area have many of the same problems — aging populations, unaffordability, health risks — plus others such a traffic and parking congestion, but that does not diminish the need for rural communities to identify problems and appropriate solutions.

Smart Planning

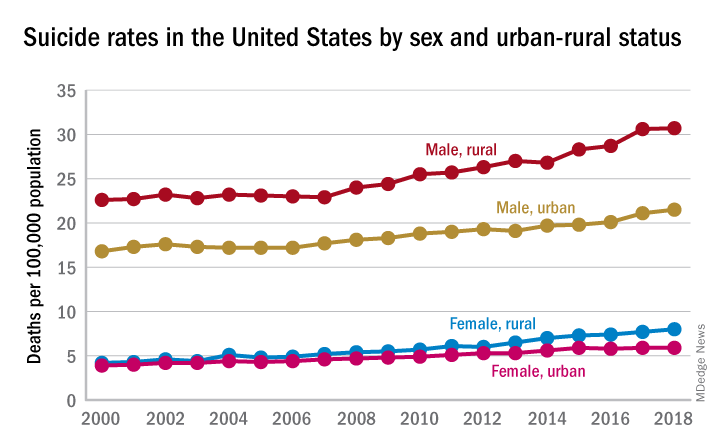

Smart planning can help solve rural problems, but it requires overcoming obstacles. Communities must identify and reform the root causes of isolation, high transportation costs, poverty, low educational attainment, health disparities, and high suicide rates, and identify practical solutions. Many excellent information resources and support organizations are listed at the end of this blog.

For example, rural communities can reduce isolation, transportation unaffordability, high traffic death rates and the health problems of sedentary living through rural multimodal planning and Smart Growth policies that improve travel options and create communities where residents can drive less and and rely more on walking, bicycling and public transit. In fact, the traditional rural village or small town of 1,000 to 20,000 residents was originally very walkable and multimodal; many of these reforms simply reestablish older planning practices; such as walkable downtowns, connected street networks, and rural bus services.

Similarly, there many local programs for improving rehabilitating existing housing for safety and energy efficiency, and building more affordable housing; diversifying local economies and supporting local businesses; and responding to unmet needs of youths and seniors. Unfortunately, many rural communities are not doing this. Rural politicians often oppose innovations, such as multimodal planning, and government programs, such as housing rehabilitation. They are enablers of disfunction, perpetuating unfair and inefficient policies.

There are many ways that planners can help rural communities achieve their goals. Most rural communities have local planners on staff, and hire planning consultants when needed to deal with specific issues. Rural community planning can be very rewarding – the responsibilities are diverse and the work can be satisfying. In my experience, there is often skepticism of outside consultants, but also respect for our expertise, particularly from community leaders – the mayor, city officials, businesses and social agency staff – who are eager to solve problems.

Many people misunderstand planners’ role. We do not tell communities what they should do, rather, we help identify what they can do, and guide a process for selecting the best options based on local needs and values. If, during a planning meeting somebody challenges you for being an outsider, don’t take it personally, simply redirect attention back to the problem that you are there to address.

For More Information

APTA (2017), Public Transportation’s Impact on Rural and Small Towns: A Vital Mobility Link, American Public Transportation Association.

Sean Berry (2010), Case Studies on Transit and Livable Communities in Rural and Small Town America, Transportation for America.

Eric Bruun (2021), Building and Managing Hierarchical Rural Transportation Networks, Rural Public and Intercity Bus Transportation TRB Conference.

Caltrans (2014), Main Street, California: A Guide for Improving Community and Transportation Vitality, California Department of Transportation.

CRPD (2016), Rural Reality: City Transit, Rural Transit, Minnesota Center for Rural Policy and Development.

FHWA (2022), Rural Transportation Planning, Federal Highway Administration.

Ranjit Godavarthy, Jeremy Mattson and Elvis Ndembe (2014), Cost-Benefit Analysis of Rural and Small Urban Transit, Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute, North Dakota State University, for the U.S. Department of Transportation.

HAC (2014), Housing an Aging Rural America, Housing Assistance Council.

Anush Yousefian Hansen and David Hartley (2015), Promoting Active Living in Rural Communities, Active Living Research, Robert Woods Johnson Foundation

Kenneth I. Hosen and S. Bennett Powell (2014), Innovative Rural Transit Services: A Synthesis of Transit Practice, TCRP Synthesis 94, Transportation Research Board.

ICMA (2010), Putting Smart Growth to Work in Rural Communities, International City/County Management Association (www.icma.org); at.

IPCS (2011), Supporting Sustainable Rural Communities, Interagency Partnership for Sustainable Communities.

ITF (2021), Connecting Remote Communities: Summary and Conclusions, International Transport Forum.

ITF (2021), Innovations for Better Rural Mobility, International Transport Forum.

Alexander Laska and Rayla Bellis (2021), Rural Communities Need Better Transportation Policy, Third Way.

Todd Litman (2021), Rural Multimodal Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Jeremy Mattson (2020), Measuring the Economic Benefits of Rural and Small Urban Transit Services in Greater Minnesota, Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute North Dakota State University; at www.dot.state.mn.us/research/reports/2020/202010.pdf.

Lydia Morken and Mildred Warner (2011), Planning for the Aging Population: Rural Responses to the Challenge, City and Regional Planning, Cornell University.

NSMM (2021), Rural Transportation, National Center for Mobility Management.

Antonio Nigro, Luca Bertolini and Francesco Domenico Moccia (2019), “Land Use and Public Transport Integration in Small Cities and Towns,” Journal of Transport Geography, Vo. 74, pp. 110–124 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.11.004).

NRTAP (2015), National Rural Transit Assistance Program (http://nationalrtap.org), Federal Transit Administration.

Reconnecting America (2012), Putting Transit to Work in Main Street America, Reconnecting America and Community Transportation Association.

Research for Community Access Partnership (ReCAP) works to increase accessibility of the rural poor through improvements to infrastructure and transport.

RTTC (2012), Active Transportation Beyond Urban Centers: Walking and Bicycling in Small Towns and Rural America, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy.

Rural Transportation Planning Clearinghouse, is the national professional association for rural transport planning professionals and stakeholders.

Rural Transportation Toolkit provides information on developing, implementing and evaluating rural transportation programs.

Small Urban & Rural Transit Center at North Dakota State University’s Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute works to increase mobility of small urban and rural residents.

Smart Rural Transport Areas Project examined ways to support sustainable shared mobility interconnected with public transport in rural areas.

SUMP (2021), Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning in Smaller Cities and Towns, Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans.

TFA (2021), Rural Communities Need Better Transportation Policy, Transportation for America.

TRB (2012), Rural Public Transportation Strategies for Responding to the Livable and Sustainable Communities, Digest 375 National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP), TRB.

TRB (2017), Best Practices in Rural Regional Mobility, National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board.

TRB (2021), Equitably Connecting Rural and Urban Populations, Transportation Research Board.

UGPTI (Annual Reports), Rural Transit Fact Books, Small Urban and Rural Transit Center (www.surtc.org), Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute.

Yvonne Verlinden (2016), Rural Complete Streets Backgrounder, Toronto Centre for Active Transportation for Complete Streets Canada.

Natalie Villwock-Witte and Karalyn Clouser (2016), Mobility Mindset of Millennials in Small Urban and Rural Areas, Small Urban and Rural Livability Center, Montana State University.

Western Transportation Institute, is the US’s largest National University Transportation Center focused on rural transportation issues.

WSDOT (annual), Rural Mobility Transit Funding Program, Washington State Department of Transportation.