Equity Plus: Toward More Integrated Solutions

Transportation equity analysis is complicated, as discussed in my report, “Evaluating Transportation Equity.” There are several perspectives and impacts to consider, and various ways to measure them. Horizontal equity assumes that people with similar needs and abilities should be treated equally, and so implies that people should “get what they pay for and pay for what they get.” Vertical equity assumes that disadvantaged groups should receive a greater share of resources. Social justice addresses structural inequities such as racism and sexism.

Because of this complexity, the best way to incorporate equity into planning is usually to define a set of measurable objectives, such as the following:

Transportation Equity Objectives

- Everybody contributes to and receives comparable shares of public resources.

- Planning serves non-drivers as well as drivers.

- External costs are minimized. Planning favors resource-efficient modes that reduce congestion, risk and pollution imposed on other people.

- Compensate for external costs.

- Accommodate people with disabilities and other special needs.

- Favor basic access (ensure that everybody can reach essential services and activities).

- Favor affordable modes.

- Provide discounts and exemptions for lower-income users.

- Provide affordable housing in high-accessibility neighborhoods.

- Protect and support disadvantaged groups (women, youths, minorities, low-income, etc.).

- Implement affirmative action policies and programs.

- Correct for past injustices.

I believe that most planners, and the people we serve, sincerely want to support these equity objectives, but the methods we use are often ineffective; many are little more than token gestures that allow decision-makers to claim that they are making an effort without imposing substantial changes. Truly effective solutions require structural reforms that can be challenging to implement but provide large total benefits.

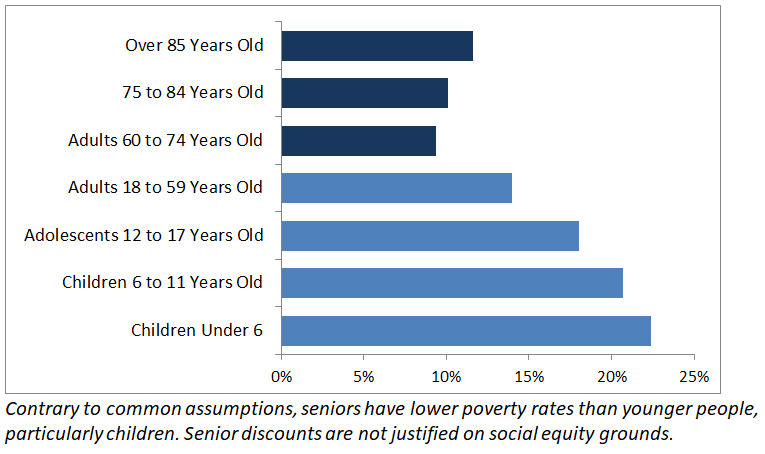

For example, senior passenger fare discounts are probably the most common and costly transportation equity strategy. Here in British Columbia these include approximately half-price transit passes and taxi subsidies, plus free ferry trips on weekdays. Why? They are justified with vague claims that pensioners struggle financially and so deserve financial assistance. In fact, seniors have lower poverty rates than for other age groups, particularly children, as illustrated below.

US Poverty Rates by Age Category

Public transportation agencies also offer discounts to other groups including youths and students, people with disabilities and sometimes low incomes, and some poverty advocates are calling for fare-free transit. These are probably more justified on equity grounds than senior discounts, but only address a small portion of disadvantaged groups’ unmet travel needs. For example, these subsidies do not help people who live in areas that lack public transit, or where those services are poorly integrated, infrequent or difficult to access, and they do nothing to reduce the large additional time costs required for public transit travel.

Certainly, people with low incomes appreciate financial savings, but transit fares are a small portion of household budgets, so fare discounts provide tiny overall savings. A much larger financial burden is the cost of owning and operating an automobile. Financially strained families could benefit much more by having better alternatives to automobile travel, plus more affordable housing options in accessible, multimodal neighborhoods.

Let’s be specific. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey, in 2020 the lowest income quintile spent an average of $101 on public transit fares, representing 0.4% of their total expenditures. If we assume that all transit expenditures are made by the 28% of lowest-income quintile households that own no vehicle, they spent $361 on public transit fares, representing 1.3% of total expenditures. These amounts are tiny compared with their $4,262 average expenditures motor vehicles, representing 15% of their expenditures. If we assume that all of those expenditures are made by the 72% of households that own vehicles, they spent $5,919 on automobiles, representing 21% of their total expenditures, far higher than the 15% maximum that is considered affordable. These are lower-bound estimates because consumer expenditure surveys overlook indirect vehicle expenses, such as residential parking costs.

To be truly equitable our transportation system should ensure that non-drivers receive a fair share of transportation investments, and communities provide a high level of accessibility to people who for any reason cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive for most trips. This requires more than targeted subsidies.

Categorical Versus Structural Equity Solutions

There are two general types of equity strategies. Categorical solutions are programs that provide special benefits to a designated group. These include, for example, universal design practices to ensure that facilities and services accommodate wheelchair users, transit fare discounts for seniors and people with disabilities, and special commuter bus services in high poverty areas. These may be useful, but as illustrated above, they are generally inadequate. For example, universal design standards are of little benefit in an automobile-dependent community that has few sidewalks, transit fare discounts are of little value in communities with minimal public transit services, and special bus services for low-income workers tend to be inefficient in sprawled areas where roads are disconnected, and homes and jobs are spread apart.

Structural solutions reform planning practices to create more compact and multimodal communities where it is easy to get around without driving. These include multimodal planning that improves affordable and inclusive modes, pricing reforms to internalize external costs, and Smart Growth development policies that create more affordable housing options in walkable neighborhoods. The table below compares these approaches.

Categorical Versus Structural Solutions

|

|

Categorical (Programatic) |

Structural (Functional) |

|

Description |

Programs that provide targetted benefits to designated groups with special needs. |

Reforms that correct unfair planning practices. |

|

Examples |

Special facilities for people with disabilities, targetted discounts and subsidies, special transit services to disadvantaged areas. |

Multimodal planning that favors affordable and resource-efficient modes, least-cost funding, pricing reforms, Smart Growth development policies. |

|

Additional impacts |

Often increases total vehicle travel which increases external impacts. |

Improves affordable and resource-efficient accessibility options, which reduces total vehicle travel and provides many co-benefits. |

|

Scope |

Provides large, measurable benefits to a relatively small group. |

Provides diverse but sometimes difficult to measure benefits to many groups. |

Categorical solutions often seem easier and more cost effective because they provide clearly-defined benefits to a specific group, but structural reforms tend to provide larger and more diverse benefits and so are generally most efficient and beneficial overall. Structural solutions can be challenging to implement, but provide diverse economic, social and environmental benefits, in addition to equity goals. Comprehensive planning generally applies both categorical and structural solutions, with emphasis on reforms that increase transportation system diversity, affordability and efficiency.

Reductionist Versus Comprehensive Solutions

This is a specific example of a broader issue. Conventional planning tends to be reductionist; individual problems are assigned to agencies with narrowly-defined responsibilities. This often results in agencies implementing solutions to problems within their responsibility that exacerbate other problems facing society, and undervaluing solutions that provide smaller but multiple benefits.

For example, transportation agencies are responsible for reducing congestion, and so often support roadway expansions, although this induces more vehicle travel and sprawl, and so tends to increase crash risk and pollution emissions, and reduce accessibility, particularly for non-drivers. Similarly, environmental agencies are responsible for reducing pollution, and so encourage vehicle electrification, although by reducing vehicle operating costs, also induce additional vehicle travel and therefore traffic congestion, crashes and sprawl. More comprehensive analysis identifies win-win solutions that help achieve multiple community goals, and so are usually more cost-effective overall, considering all impacts.

In fact, some of most effective ways to help disadvantaged groups are not generally classified as equity strategies. They include, for example, least cost transportation planning that allows funds currently dedicated to road and parking facilities to instead be used to improve non-auto modes, complete streets policies which ensure that all streets accommodate diverse modes and activities, and parking policy reforms that that reduce the subsidies that car-free households must pay for costly parking facilities they don’t need. Because they provide diverse benefits, these strategies can gain support from numerous interest groups including environmentalists who want to reduce pollution emissions and habitat displacement, developers who want to build more compact housing with unbundled parking, and public health professionals who want to create more walkable and bikeable communities.

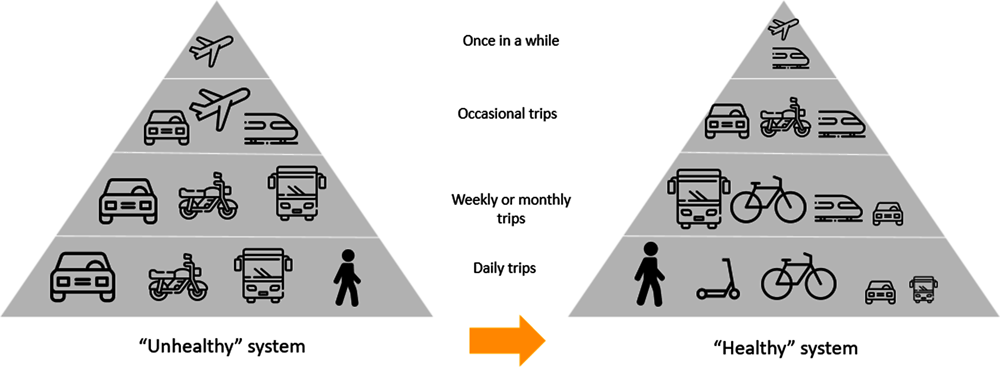

In general, automobile dependent transportation systems are inherently inequitable and inefficient because they fail to serve non-drivers and they favor expensive and resource-intensive transportation over more inclusive, affordable and efficient alternatives. This is not to say that automobiles and bad and should be forbidden, but everybody, including motorists, benefit from multimodal planning that favors diverse and efficient travel options: walking, bicycling and micromodes for local errands; ridesharing and public transit for travel on busy urban corridors; and unsubsidized automobile travel for use when it is optimal overall, considering all impacts.

Examples of Integrated Thinking

I am happy to see that several major organizations have recently published documents that support integrated planning that includes equity objectives.

- Better Access to Urban Opportunities: Accessibility Policy for Cities in the 2020s, by the London School of Economics and the OECD for the Coalition for Urban Transitions, identifies policies to integrate climate emission reduction and social equity goals into pandemic recovery programs by creating more accessible, transportation efficient cities.

- Transport Strategies for Net-Zero Systems by Design by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), applies a well-being lens to transport emission reduction planning. It concludes that induced demand, urban sprawl and the erosion of active and shared transport modes results in car dependency and high emissions. It provides policy recommendations to reduce emissions while improving well-being including radical street redesign, more compact development and favoring shared mobility. It concludes that these policies increase the effectiveness and public acceptability of carbon pricing and vehicle electrification.

- Draft Advice for Consultation, by the New Zealand Climate Change Commission evaluates emission reduction strategies based on the degree they support other strategic goals. It recommends urban planning reforms, active mode improvements, freight management, reliable and affordable shared transport, plus electric or low-emission vehicles.

- Co-Benefits of Climate Action is a research project that maps climate action co-benefits, showing the complementary nature between climate innovation and other actions that contribute to more sustainable development pathways.

- LADOT Strategic Plan, by the city of Los Angeles, addresses five major goals: equity, health and safety, sustainability, economic growth, and COVID action. To accomplish this, a city which was once famous for its car culture is now implementing multimodal projects and integrated transportation and land use planning.

- Climate Emergency Action Plan, by the city of Vancouver, which will also achieve equity goals by making low-cost sustainable transportation options easy, safe, and reliable.

These examples illustrate opportunities for structural reforms that help achieve equity objectives plus other economic, social and environmental goals by creating more affordable and resource-efficient transportation systems, and more compact, multimodal communities where it is easy to get around without driving.